The Complex Art of Being a Biracial Actor

It can be difficult to navigate the world as a biracial person. But being a biracial actor in the theater world is a unique struggle. It’s an entirely different art form; one that brings the question of “which box do I check?” to a whole new level.

I have loved theater, specifically musical theater, since middle school. In my teen years, I was lucky enough to play some great roles. A “hot box” dancer in the 1950’s classic, Guys and Dolls. Eve (of Adam and Eve) in Children of Eden. Lucy, a “lady of the night” (*wink*) in Jekyll & Hyde. None of these roles took my race into account. I was just another kid auditioning for and performing in musicals.

Sure, I was one of three Black people in a musical with a hundred kids. But I never felt like an outsider because most people around me didn’t acknowledge my skin color. I just sang the way I wanted to sing. I danced the way I wanted to dance. My confidence in my skills grew as I made my way through high school.

Then I entered the world of community and professional theater, and I learned that my darker skin walked into any audition room first and foremost before any of those skills.

I quickly learned that there is an expectation of Black women in musical theater, and of Black women in music in general. I’m sure you’re familiar. If I tell you there is a Black woman singing, close your eyes and tell me what it is that you imagine hearing. Aretha Franklin? Whitney Houston? A huge Black voice, belting from the depths of her soul, riffing up and down the scale and somehow hitting notes between notes that you didn’t realize existed along the way? Yes. I believe that’s what most people imagine hearing from that imaginary Black woman on stage or at a microphone.

I have brown skin (and I am Black) so I naturally get called in for the Black shows. The Color Purple. Hairspray. Parade. Aida. Shows that I love, but shows that have, often times, made me feel inadequate.

Why is that? Well, my voice can be strong, but it’s not big. My voice can sing both high and low, but it can’t riff up and down the scale with abandon. My voice is just not stereotypically ‘Black’, even though I’ve always felt pressured to make it sound that way. And, most of all, I am not 100% Black.

These shows have highlighted, in my own mind, the insecurities that come with and from being mixed. I am partly Black, so I fit in. But I’m not all Black, and it shows.

As a biracial girl with skin the color of coffee mixed with cream (a Once on This Island reference for all you theater nerds), I found myself doubting my place in the Boston theater scene. I wouldn’t be playing White roles without having people dig into the meaning behind the casting choice. But by looking only partly Black and not “sounding Black,” would people see me as a fraud in Black shows?

A Nightmare Come True

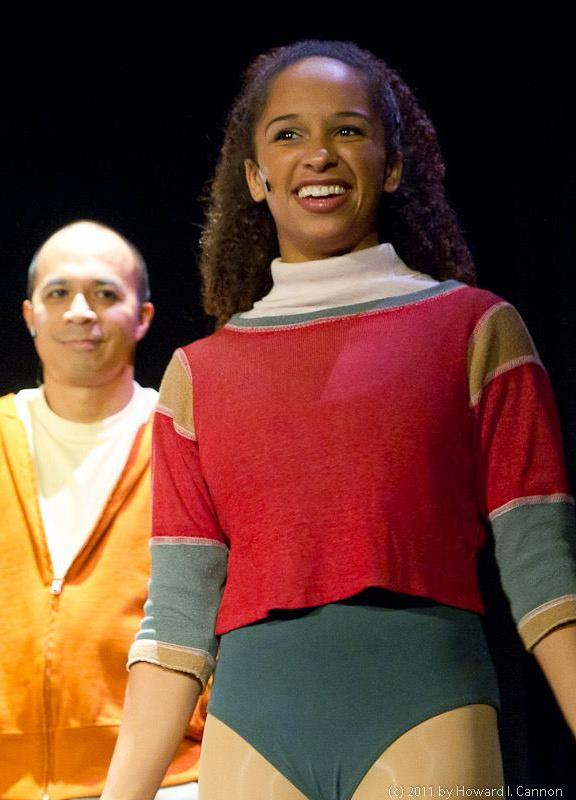

I was in a production of The Color Purple several years ago. It was my first experience performing with an entirely Black cast. And from day one of rehearsal, I felt like I didn’t belong. Even though I grew up with two Black parents, even though I grew up going to a Black church every Sunday, and even though my racial background fully qualified my presence in the show, I felt like an outsider. My skin felt like the lightest in the room (even though looking at the picture now, I can see that I do blend in), and my voice certainly didn’t sound like anyone else’s.

And then, my nightmare of being identified as the fraud in the group became reality.

We performed one afternoon for a group of mostly Black and brown kids from Boston public schools. After the show, we had a talkback where the kids could ask any questions they had of the cast. Toward the end of the session, one bold kid stood up in the back and said:

“I have a question for the daughter.” I was playing “the daughter” at the end of the show. “Why aren’t you as dark as your mom or everyone else?”

My heart stopped. Then I remember saying something to the effect of, “Black people are a beautiful rainbow.” There was an awkward chuckle that scattered around the room. And then the moderator of the talkback moved on to the next topic.

Why aren’t you as Black as everyone else? I could feel it. The audience could see it. Out of the mouths of babes.

Authentic Casting

There are a lot of conversations going on right now about how to hit the right notes with diversity and inclusion in theater. After the murder of George Floyd, a racial reckoning gripped the country as a whole and also emboldened a community of BIPOC theatremakers to point out the many issues plaguing White American theater. People are challenging and even criticizing the notion of “colorblind casting.” And there are debates raging about authenticity in casting. (I’m linking off to other excellent articles on these topics because I would get extremely off-topic if I dove into these matters too deeply here.)

But my feeling is that most of these conversations neglect the existence of biracial and multiracial actors. I have seen a whole lot of opinions out there, but I have yet to see anyone offering clear guidance for people who straddle two or more racial worlds.

Let’s first break down what’s important about any given actor portraying a specific role. Theater, like film, is a visual medium. So the way an actor looks is often a crucial part of the story. You have to look a certain way in order to portray certain characters effectively to the audience. Ma Rainey has got to appear as a big Black woman to tell that story, for example. Leo Frank in Parade has to be a White man in order to tell that story effectively. You’re not going to have a White woman play Effie White in Dreamgirls. And you’re not going to have a Black man play Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof.

So when it comes to visual representation, where does a biracial person fit in?

I can’t play White characters without the casting choice being about ‘diversity’ or ‘colorblind casting’, but when I play Black characters, the expectations that come along with those roles feel so heavy. And the number of times I’ve played a Latina person because I fit into the picture visually and speak passable Spanish is a topic for another day.

I will even admit to being cast as one of two people of color in a production of Miss Saigon in my early twenties. That production featured a grand total of one Asian person (the little boy who played Tam). And yes, while the people involved in the production were lovely, I cringe every single time I recall it.

That brings me to another point being shouted about, both in theater and in television and film: authenticity. Theatremakers and theatergoers with their sights set on diversity and inclusion want to make sure that marginalized groups get the opportunities to tell their own stories. We want to see Black people in Black roles. Asian people in Asian roles. Latinx people in Latinx roles.

It doesn’t matter if, say, Emma Stone can pass as 1/4 Asian. The argument there is that she is not at all Asian, and therefore casting Emma Stone in a part-Asian role in the movie Aloha was inappropriate. The argument is valid for so many reasons that Stone herself recognized.

But then there are more nuanced instances, like when Zoe Saldana played Nina Simone in a 2016 biopic. Saldana originally defended her right as a Black, biracial woman (granted, of Dominican and Puerto Rican descent) to play Nina Simone. But more recently, she has apologized, stating, “I know better today and I’m never going to do that again.”

Now, these are Hollywood examples, and I’m talking about theater at a more local level. But, when it comes to authenticity, is it inauthentic to play a role if you, as the actor, are not the same racial makeup of the character in question?

A biracial actor may be Black, and not able to pass as White. But what happens when Black, biracial actors don’t “look Black enough” to play Black parts, or when Asian, biracial actors don’t “look Asian enough” to play Asian parts? Talk about identity issues. It’s complicated stuff.

I tend to look Black enough to play Black characters, for the most part. And I am partly Black, so I have been cast as Black characters without facing much criticism. However, I have a friend who is half-Chinese and who rarely gets cast in Asian roles. Even though she is actually a Chinese, biracial woman, she is often told that she doesn’t quite “read Asian” on stage, and therefore doesn’t get considered. In fact, she’s been more successful at landing Latina roles because of the way she looks.

I also have a White-passing biracial (Black and White) friend whose voice is much more stereotypically “Black” than mine (man, can she sing). But she has confided in me that she rarely gets the chance to portray Black characters because her skin appears too light on stage.

If we’re judging casting for being “authentic,” these women could play roles that reflect their racial identities. But physically, their skin has kept them from being cast in Asian or Black roles respectively. And on the flip side, a Latina woman, for example, could perhaps appear to be Black on stage. Her skin color might help tell the story of the Black character she’s portraying. But is it an authentic portrayal? Is it more authentic than a lighter-skinned Black, biracial woman’s portrayal would be?

The Future of Biracial and Multiracial Actors

I don’t have many answers. I do have a lot of questions that bounce off of each other in my mind. And the time seems ripe for getting those questions out of my own head and starting to have more nuanced conversations about them.

What happens if (okay, let’s be real, when) my son gets into theater? He is Black, White and Jewish. What roles will he be able to play? He is Jewish, but is he “Jewish enough” for Fiddler on the Roof? He is Black, but is he “Black enough” for The Color Purple? He is a beautiful mix of ethnicities, and I can’t wait to share and explore his various identities with him. But what does his multiracial identity mean for him in this current theater environment?

He may look like he belongs as a character in many stories. But is it “authentic” for him to be playing roles that don’t line up with his own racial identity? He may look like a Bernardo in West Side Story, but he’s not Latino, so that wouldn’t be authentic. But should he be discouraged from playing roles that do line up with his racial identity because he doesn’t quite look the part? His skin is lighter than mine, so unlike me, his portrayal of a Black character might raise more eyebrows.

My head spins every time I let these thoughts spiral.

I have to acknowledge the privilege involved in being White-passing. If you can pass as White, then you’ve obviously got a world of opportunity regarding the roles you can play in musical theater (even though you’re also putting an entire part of yourself to the side because others can’t “see” it).

But if your skin is a lighter shade of brown, where do you belong in the world of theater as it stands today?

I believe one major answer to all of the above is that we need more stories. We need more plays and musicals that factor in the nuances of our identities. There are important stories about Black and White people that should continue to be told on stage. But rather than everyone else trying to squeeze themselves into a category or racial identity that makes sense on stage, wouldn’t it be a beautiful thing to have categories and roles custom made for us? Wouldn’t it be great to have our stories told on stage too?

There are Black stories with roles that I’ll continue to audition for (ones that I feel I could play authentically). And I think my response to that boy at The Color Purple talkback was more poignant than I gave myself credit for at the time. Black people are a beautiful rainbow. It’s important for all of those gorgeous colors to be reflected as authentic on stage, because that’s real life. We don’t all look or act or sing the same.

But wouldn’t it also be great to not be cast in the name of “colorblindness,” or with the thought of “her brown skin will do,” or as a “Black-enough option,” but instead, for a change, have a biracial role to audition for? It never occurred to me, until recently, how amazing that would be. How wonderful it would feel if a role didn’t completely ignore my skin color, and didn’t feel too big for me or make me feel like a fraud, but instead told a story about my racial identity.

While biracial and multiracial actors wait for more stories to come down the pipeline, we’re just stuck here trying to figure out which box to check, or which role to try to squeeze into. If we want to be actors in the theater world today, we have little choice in the matter. And in the meantime, I’m just going to keep on writing my stories down and hoping that other mixed people are doing the same.

Wow! My head is trying to catch up with all the points you raise. Thank you for raising them. There are no easy answers yet, but the discussion and action steps need to keep on. Thanks you!

Thank you for posting this. I am biracial (Haitian, Polish, Russian Jew) and am on the lighter side. Casting is a trip. The only biracial role that I have played is “Melody” in Neighbors- a brilliant play by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins. Other than that, I’m not black enough for black roles and not ethnic looking enough for a token. It’s a mess. Not sure what else to say, but the only thing I could think of is pursuing roles where ethnicity doesn’t matter (does that exist?) or writing own my own work (but like… I didn’t trying for 20+ years to be a writer..).

👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾

You verbalized so much of what I and my family talk about OFTEN-Thank you Kira!

I still haven’t had the opportunity to “work” with you yet… but, now I want to even more! Thank you for your voice, and sharing your thoughts… many of which we can relate to, and many we have experienced. May we grow through all of this to become better humans, and artists in the near future ❤️